Pacing encourages you to operate within your physical and mental limitations, avoiding activities that make your symptoms worse. Everyone is different, so it is a gentle and individual way of managing energy and lifestyle, aimed at stabilising symptoms and preventing the ‘boom and bust’ vicious circle of over‐activity then relapse. Pacing is usually self‐managed by young people however they can be assisted by parents, carers or education staff. Pacing focusses on making slow and gradual increases in activity‐ as and when you feel ready to take on more.

What does it involve?

Pacing involves cutting up activity into manageable chunks and switching between physical, mental, social and emotional activities throughout the day. And all these activities should have periods of rest planned around them to keep your energy levels as high as possible, and make sure you don’t become over‐tired. This means taking notice of what your own particular ‘warning signs’ are, and stopping your activity before you reach exhaustion point.

- Physical activity includes walking, playing, shopping and anything that involves moving around.

- Mental activity can mean watching television, using a pc or mobile, or doing school work.

- Social or emotional activity might be time spent with friends; or being upset, excited or anxious. Coping with social occasions or being emotional can use up a huge amount of energy.

- Rest is quiet relaxation time with no television, radio or computer on. It is important to get enough rest, even if you feel you want to keep going and ‘work through’ your symptoms.

- Resting pre‐emptively (that is, in a planned way, not just when you really need to) throughout the day is likely to help you keep your energy levels as high as possible.

- Rest means lying down with your eyes closed, doing nothing except letting your mind wander – with no interruptions.

- You may find it helpful to practise relaxation techniques (such as visualisation, meditation or slow deep breathing), or listening to relaxation music (listening to dance music is definitely not relaxation!).

The main thing to remember when you are pacing is not to overdo any kind of activity or rest for too long if it can be avoided. By stopping before you get exhausted, your recovery time will usually be fairly short (within hours). For some people, carrying on to the point of exhaustion or beyond can mean taking days to recover back to a ‘normal’ level. Total bed‐rest is not recommended for most young people (however there are exceptions for severely affected young people its unavoidable).

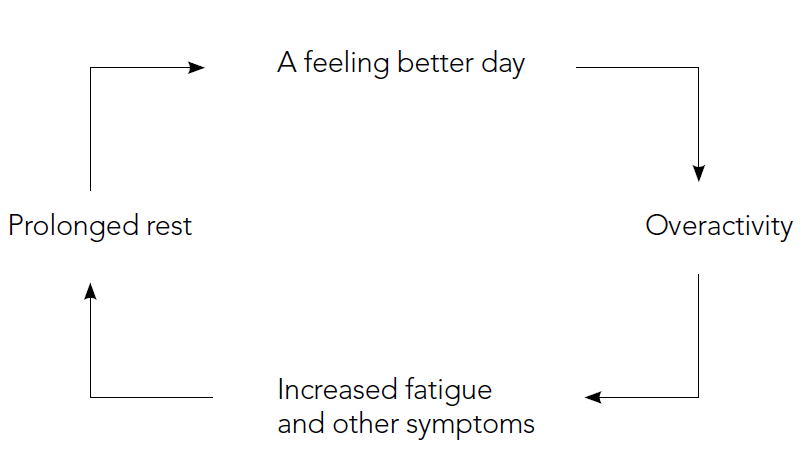

A key frustration for many people is that symptoms fluctuate. Some days you can feel slightly better and at other times you can feel a lot worse, perhaps for no obvious reason. When symptoms reduce your activity levels it’s very easy to try to make up for lost time on better days. But cramming in too much activity on a day when you are feeling better often leads to a setback in your symptoms. It becomes a vicious circle that is damaging to the recovery process and frustrating and unpleasant to live with. This is sometimes called ‘boom and bust’ or ‘activity cycling’ and it’s easy to fall into this cycle:

Pacing helps you to take a more even path through your symptoms. You can achieve a stable level of activity that is realistic to your health and that you can sustain without facing harmful consequences.

Finding your ‘baseline’:

The Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health (RCPCH) Evidence‐based Guideline for the Management of CFS/ME in Children & Young People 2004 (page 44) says: “a baseline of activity that the child/young person can manage even on a bad day should be established.”

This means you need to work out how much activity you can manage every day, even on a bad day.

At first, you may not know what you can and can’t do, or how long for, without exhausting yourself and setting off your symptoms. So finding your baseline will probably take some time, and some trial and error! Remember, your total activity for a day won’t just be physical – it will be mental, social and emotional, too. This is why it’s important to keep an activity diary to track activity and rest, and you they feel each day.

You’ll need to record all activities and rest periods. Your activity diary will give you a clear picture of what you can manage (and for how long) without getting exhausted, and which activities may tend to make your symptoms worse.

Keeping a diary can seem like a bit of a chore at first, but it’s going to help you find your baseline, and will help you to spot anything that may be causing problems. Having this record of all your activities and rest will also show you things you might not have noticed otherwise. It can be helpful if a parent/carer/education staff member is involved in your activity diary, as they often notice things that you might not see yourself.

Maybe some time you thought what was a rest period wasn’t really, because you were chatting to a friend. Or perhaps they’ll see your progress where you hadn’t realised how well you were doing.

Over 4 or 5 weeks, you’ll be able to see a pattern that shows you how much activity you can manage (and how much rest you need) on average each day, good or bad, for at least five days out of seven – and preferably every day. This is your first baseline. Everyone’s baseline is different; there is no ‘one size fits all’.

If you can follow your baseline for three or four days, but then find you are exhausted for the next three or more days, then your baseline is too high. This means you’ll need to cut back on activity somewhere, which could mean:

- Slightly reducing how long your activities take to complete.

- Looking at what kinds of activities you are doing – have you got the right balance of physical, mental, social and emotional?

- Having slightly longer or more frequent rests.

- Making sure that rest periods aren’t including any mental, social or emotional activity.

Building activity:

Once you’ve found your baseline and have been able to stick it consistently, you can start to carefully increase activity in very small steps, while keeping a note in your activity diary of what happens. If your symptoms worsen, or new symptoms start to show, you will need to go back to your baseline for a while before trying again.

“The patient should start with a level of activity they can manage, even on days they are feeling particularly bad and are advised not to do more on days they are feeling slightly better... Once the child/young person is achieving this amount of activity consistently then the amount of activity can be gradually increased and the rest decreased”.

The Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health Guideline, page 45

Building activity, how much and how often, is the hardest part of a pacing programme; and one suggestion is to try increasing activity gradually by 10 or 15%. So a school session of 40 minutes would go up to 44 or 46 minutes. It definitely doesn’t mean going from one session to two, as that would be a 100% increase! It’s really important to keep these percentage increases in mind, as doing too much too soon can increase the risk of relapse. If you are doing lots of short spells of activity, you might want to try increasing half of them by 10‐15% for a few days, seeing what happens, and if all is well, then increasing the other half by the same amount. This saves you having to increase everything all in one go. You will need to find out what works best for you – and your activity diary will help you keep track.

What you don’t want to do is set yourself targets and make regular increases regardless of how you are managing. Pacing means that you are the one who sets your baseline – and once you have made an increase that you have been able to stick to successfully, you are the one who chooses when you are ready to add another increase. You are in control of when and how each step is taken, with the support of your parent, carer or understanding professional.

Benefits of pacing:

Pacing means you decide for yourself whether you use physical energy, mental energy or social energy on a particular day, or a mixture of all three. You’ll soon find that you can probably switch types of activity to get the most from your active periods, as you discover which activities are the least or most tiring for you. You’ll learn about your body, and take responsibility for planning your own activity and rest programme… you can start taking more control, rather than your symptoms always controlling you! Pacing is all about building up carefully, and making sure you take planned rest between activities to avoid boom and bust. And as there are no set times for moving forward, there is no success or fail – you make changes based on your knowledge of your own body. Which means listening to it yourself, and understanding what those signs and symptoms are telling you.

What are the challenges with pacing?

Pacing isn’t easy. It takes some practise, and you need to be willing to go through the ‘trial and error’ part at the beginning. Because there are no rules, it can be frustrating sometimes, too.

Keeping your activity diary is essential, as it’s your record of what you’re doing, how your body has reacted – and as the weeks go by, the progress you’re making. Even the tiniest steps count.

Pacing also means accepting your limitations, and coming to terms with the way you feel about how your symptoms have affected you. You may already have done this – it may still be a process you are working through, hopefully with help from good support from others you will work your way through the challenges. Being responsible for your own plan isn’t always easy when you’re also copying with your symptoms.

Other common problems with pacing:

- You may be tempted to rush progress and risk falling back into boom and bust;

- Not taking pre‐emptive (planned) rest breaks;

- Counting television, radio, computer games, texting, social occasions as ‘rest’ (they’re not!).

- Not re‐pacing after illness or a relapse;

- Feeling nervous about moving forward once you’ve found your baseline.

Most young people who do pacing say their activity diary helps them to learn about their own individual symptoms, and that it gives them a sense of control back over their life. You have to do it properly, and you have to want to do it for yourself. Pacing takes a lot of commitment – from the people who support you, as well as yourself.

References: